In Pursuit of Truth

“There is nothing more ancient than the truth” — Rene Descartes

Searching for truth is a human trait. It transcends gender, race, generations and nationality. It plays a role in science, politics, law… and most importantly, in our everyday life.

What is truth?

When Wikipedia starts defining a concept by saying “Truth is most often used to mean…” you know it must be hard to do so. Some philosophers say truth is “unable to be explained in any terms that are more easily understood than the concept of truth itself” and some try to define it through correspondence, coherence or consensus theory. We won’t dive into so much detail on the definition, as it could take hundreds of pages to do so. It can be more interesting to look at how we interact with what is thought to be true.

Our Relationship with Truth

Let’s take a look at this from two different perspectives: the analog world and the digital world.

Truth in the analog world

The simplest way we as humans have been in contact with truth is by associating what we see to facts. “ Seeing is believing ” they say. This hasn’t changed much throughout centuries; a caveman instinctively believed what he saw to be true the same way a hispter in Los Angeles would do today.

Another source of truth for people has commonly been religion. What God speaks, through holy writings or prophets, is believed by his followers to be true and it makes little sense to question it. So many lives have been lost fighting over opposing religious truths! It could be argued that factors such as inner peace, moral calm or even fear also come into play when associating religious beliefs to facts.

Another ancient way of pursuing the truth has been to rely on trusted people. Friends, family… From a young age, we take most of what our parents tell us to be true: we might grow up to disagree more and more with them over whatever topic, but it’s rare to naturally associate the information that comes from them to lies. It was also common in previous times for news to be announced by someone reasonably trustworthy shouting around the streets of a town. A funny cultural story about true/false conjectures we’ve probably all heard some time is The Boy Who Cried Wolf.

A whole range of professions, industries and cultural traits have been built over the search for truth: we’re talking about media. People want to know what’s going on, we want stories, we want facts and we have evolved to want them from trusted sources. In this great piece, Kerem Ozkan, a Witnet community member, explores the business model of truth. We must reflect on how trusted sources of truth have been manipulated, corrupted and biased over time: it’s not something to take lightly.

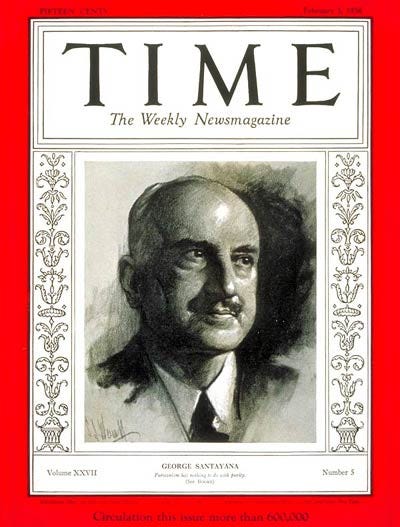

“History is a pack of lies about events that never happened told by people who weren’t there” — George Santayana

Analog world truth is a very interesting concept. It is constantly confused with opinion, evidence, or belief. This has driven a lot of interesting thoughts about its role in history, with popular leaders like Napoleon stating “History is a set of lies agreed upon.” On the same day that construction began on the Berlin Wall, German Communist leader Walter Ulbricht publicly claimed that “Nobody has the intention of building a wall.” Many people have taken advantage of these general confusions to game systems into their advantage. The use of fake news to influence the 2016 U.S. presidential election is a great example of political incentives to lie. Other incentives can be financial fraud, identity theft…

It’s not so hard to find an incentive, in a given system, for some party to lie. This brings us to digital world truth and, more precisely, to The Oracle Problem.

Truth in the digital world

Computer systems have historically relied on trusted sources to feed them data. The code would not analyze if this data is true or false; the concept of truth relies on the developer or software feeding this data into the system. This means that until now, the mechanisms for doing so relied on trusted sources. Trusted sources are corruptible, censorable, and can simply fail. This is known as The Oracle Problem, a topic that has been hot in the crypto community for some years now (in this case, Oracle doesn’t relate to the future prediction meaning it also bears) . An oracle is a system that enables software to retrieve verified data. For a solution to really work with decentralized infrastructure, it needs to be designed in a trustless manner. And that’s where Witnet comes in! Witnet makes (not-so)-smart contracts truly smart by enabling them to communicate with any source of data available online. It does so in the trustless, decentralized way described in the whitepaper . What sets it apart from other solutions is its decentralized network of nodes operating a headless browser, incentivizing telling the truth over trying to lie.

The crypto space is building the infrastructure for a trustless society. Cryptocurrencies aim to enable trustless exchange and store of value, as well as trustless computing, with the possibilities all that implies. In this environment, it makes sense to develop a solution for trustless data retrieval to empower these systems even further. Witnet does this in a decentralized, trustless, censorship resistant way.

We’re building a world where truth moves away from opinion and closer to facts. Maybe, some time in the not too distant future, the debate over what’s true won’t even happen.

This feels like something that matters?

Thanks a lot for reading! You can also:

- Kauri original title: In Pursuit of Truth

- Kauri original link: https://kauri.io/in-pursuit-of-truth/5b01bd8fb4554597a380a0fe0c13e62a/a

- Kauri original author: Witnet (@witnet)

- Kauri original Publication date: 2018-11-19

- Kauri original tags: none

- Kauri original hash: QmWq1UqvfgyiaMy8k3jHwMsfrhCC4C1reKjz5uuVwpyFjB

- Kauri original checkpoint: QmYRYAA1TRyDiXS6uLXdt6qS8AnW63tqJHYpUQKrdyNz7h