On Oracles and Schelling Points

An oracle refers to the element that connects smart contracts with data from the outside world. Any data point outside the contracts’ blockchain is not accessible by design, so an oracle is needed to feed them information from external sources. For a blockchain oracle to be fully decentralized, its network of nodes must reach consensus on the state of the world for a given request, event or decision in a decentralized and trustless manner.

What was the weather in Helsinki yesterday at 4 p.m.? Who won the World Cup semifinal? Did Donald Trump win the presidential election by a vote margin larger than 5%?

Nodes in an oracle network must agree upon the answer to these kinds of questions. Therein lies the challenge.

Schelling Points

In 1960, Thomas Schelling introduced in his book “The Strategy of Conflict.” The concept of Focal Points was presented as “each person’s expectation of what the other expects him to expect to be expected to do.” A bit confusing, right? A focal point (or Schelling point, as it has later been renamed) is a solution people will tend to choose when unable to communicate, because it seems to naturally or specially make sense for them. Schelling provides a common example to illustrate the concept of focal points:

“Tomorrow you have to meet a stranger in NYC. Where and when do you meet them?”

He asked a group of students that exact question, and found out that the most repeated answer was:

“Noon at (the information booth at) Grand Central Terminal”.

Why would this happen in an experiment where anyone was able to choose any time of the day and any place in a city with as many possibilities as New York? There was no special price attached to that solution that made it more attractive than others. Yet something about it (its tradition as a meeting place, its relevance to the city) made it a natural focal point for a number of students.

Consensus

To understand how Schelling schemes provide a way for oracles to achieve consensus, we’re going to take a look at three different oracle formulations. In chronological order, Truthcoin , SchellingCoin and Witnet provide us with different approaches of mechanism designs for nodes of an oracle to agree upon a certain result, solution or answer.

Truthcoin

Truthcoin presents a peer to peer oracle and a prediction market that is fed information from an oracle in order to resolve markets. As Sztorc put it:

“An ‘oracle corporation’ model attempts to guarantee that a group of self-selected, anonymous, greedy users will always resolve contract-outcomes honestly. Outcomes are established by weighted-vote…”

In Truthcoin people owning VoteCoins say which outcome they believe to be true, and the market closes based on the outcome achieving vote majority (>50%). The mathematical calculation of outcomes is worked out by performing singular value decomposition on the Vote Matrix, a matrix composed of the voters’ decisions on a series of outcomes.

When voting, Sztorc points at two factors that influence human behaviour. The first is search costs, or how long it takes you to “google” the true outcome of a prediction market. The second one is salience. That’s where Schelling comes in.

Salience is the psychological perception of uniqueness which Schelling pointed out when studying focal points. Grand Central Station proved to be a salient meeting place in his experiment. It’s an awareness of shared human psychology that Sztorc says “ minimizes shared mental costs ” and provides an incentive for people to not deviate from the profitable-truth-seeking majority. Effort-wise, the cheapest thing a voter can do is copy the ballot of true answers.

Attacks

Malicious actors will always try to coordinate in ways that are harmful for the network if they can get a profit from it. In order for the incentive scheme built into the network to be effective in spite of these attacks, malicious actors must not be able to communicate with each other in advance and conspire.. Truthcoin keeps votes anonymous and introduces the concept of the “ double-agent incentive”.

The double-agent incentive explains that voters have an incentive to falsely claim that they intend to attack.

“As long as >50% of the Voters are honest overall, each Voter wants to minimize the number of honest Voters. This discourages cartels and ‘voting pools.’ The reward is indeed highest at 51% agreement.”

A coalition of attackers will never be truly sure of how many voters they control, so any voter has an incentive to let minority groups lie (and make them think she will lie too) and earn a higher reward for telling the truth.

SchellingCoin

Vitalik Buterin presents SchellingCoin as a “ decentralized data feed ” for smart contracts to access information from the outside world, presenting a simple example regarding the ETH/USD price.

During an even-numbered block, all users can submit a hash of the ETH/USD price together with their Ethereum address.

During the block after, users can submit the value whose hash they provided in the previous block.

Define the “correctly submitted values” as all values N where H(N+ADDR) was submitted in the first block and N was submitted in the second block, both messages were signed/sent by the account with address ADDR and ADDR is one of the allowed participants in the system.

Sort the correctly submitted values (if many values are the same, have a secondary sort by H(N+PREVHASH+ADDR) where PREVHASH is the hash of the last block).

Every user who submitted a correctly submitted value between the 25th and 75th percentile gains a reward of N tokens.

Basically, in the example users provide their price for the given exchange, their claims are verified, and those whose answer falls between the 25th and 75th percentile are rewarded by the network. Buterin, like Sztorc, states that the truth is the most powerful Schelling point. That’s the reason the protocol incentivizes everyone to provide the same answer as the rest of participants in the network. But unlike Truthcoin, which defined final answers by simple majority, SchellingCoin applies statistical percentiles to leave out answers that deviate too much from the median.

Attacks

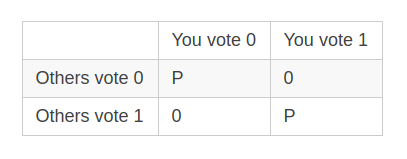

Regarding collusion attacks, the first one that Vitalik explains is the already mentioned possibility of an entity controlling more than 50% of all votes. This attack is disincentivized in the same way the attack on Truthcoin was (double agent incentive). Discussions around SchellingCoin gave birth to an attack that gathered a lot of attention in the Ethereum and cryptoeconomics community: the P + epsilon Attack (I recommend reading the full piece, as it also goes through a series of possible (failed) solutions to the problem). The attack goes as follows: imagine an entity that wants to gain control over the outcome of a certain vote. Without an attack, this would be the possible payoffs of a vote for any voter:

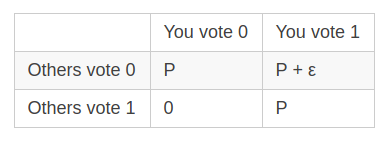

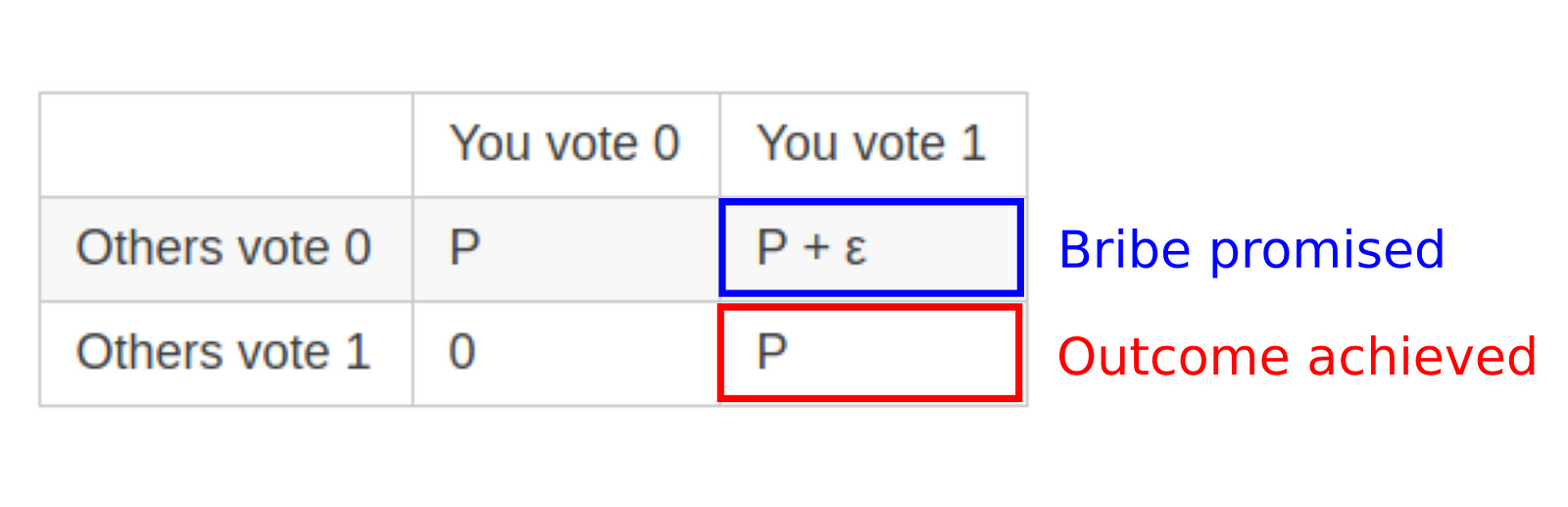

There are two possible Nash equilibria (situations where voters get a reward for their action) and those are where there’s a majority of voters agreeing on the same solution, be that 0 or 1. Yet, a briber comes and introduces the following proposition: “ I will pay out X to voters who voted 1 after the game is over, where X = P + ε if the majority votes 0, and X = 0 if the majority votes 1.” Now, the payoff matrix looks like this:

Now, voters have a clear incentive to vote 1 no matter what . Assuming voters are not altruists but financially motivated individuals, they will vote 1. Therefore, the attacker will get everyone to vote as wished without actually having to pay anything . The attack is free.

Is this attack feasible? Technically speaking, it’s as simple as making a smart contract deliver the bribe based on the vote results. In practice, Buterin points out:

“Proof of work has survived despite this flaw, and indeed it may continue to survive for a long time still; it may just be the case that there’s a high enough degree of altruism that attackers are not actually 100% convinced that they will succeed — but then, if we are allowed to rely on altruism, naive proof of stake works fine too. Hence, Schelling schemes too may well simply end up working in practice, even if they are not perfectly sound in theory.”

Witnet

Witnet is a decentralized oracle network. Unlike the other two proposals explained in this post, Witnet’s “voters” are actually computer nodes (and not humans) called “witnesses” fulfilling inquiries from the network as to what the answer or result to a certain request is. When a request is sent into the Witnet network, randomly selected nodes run a headless browser that will retrieve the desired data point (from an API, or any source available online). The protocol is designed to deliver verifiable data by “comparing and combining a number of likely conflicting claims coming from a plurality of anonymous players.”

This protocol is called Truth-By-Consensus. Truth-By-Consensus sets incentives for network participants to become witnesses — that is, to perform tasks honestly and maximize their revenue (short term profits) and reputation (long term profits). It is based on Singular Value Decomposition.

“The purpose of SVD is to analyze a matrix containing all the claims brought during one epoch and reveal and sort its effects by influence, detecting and dropping outliers and collusion (coordination) in the process.

To measure coordination, SVD uses the first score from a weighted principal components analysis. This column represents the degree to which each miner’s claims differ from those of a theoretical maximally representative of the co-variance across all miners and claims.”

Although an oracle of a different nature, many parts of Witnet’s concept derive from Truthcoin’s design. The double-agent incentive is also present in Witnet’s design, incentivizing witnesses to keep claims secret and even lie to a potential briber. As also seen before with Truthcoin, once >50% of the witnesses are honest, witnesses have an incentive to minimize the number of fellow honest voters and maximize rewards.

Attacks

Witnet intends to detect and penalize collusion by focusing on economic incentives within the protocol. The fact that witness nodes accumulate non-tradeable reputation acts a long term incentive to avoid lying. This way, they not only have the risk of losing short and mid term rewards but also of being deprived of the revenues involved in future tasks that are assigned based on reputation distribution. The introduction of reputation punishment changes the game’s payoffs for witnesses.

To avoid harmful majority collusion, Witnet provides a mechanism where participants in the network “(1) have no way to identify each other, (2) have no way to communicate with each other and (3) can not prove the content of their claims to others before the reputation and reward redistribution is made”, as said in its whitepaper.

This also fights possible P+epsilon attacks. The Witnet protocol doesn’t give participants a chance to reveal or prove the value of the claims they voted for. Participants could then accept the bribe, tell the truth to the network, and lie to the briber in order to claim both the reward and the bribe. Claim anonymity on every epoch provides another case of Sztorc’s double-agent incentive, leading the briber to most-likely waste their resources since witnesses will try to maximize revenue by voting the truth in order to get a reward while also telling the briber they lied in order to get the bribe.

Schelling’s Edges

Schelling coordination schemes have been the subject of research since first introduced some decades ago, most generally validating the efficacy of focal points in coordination games. Let’s take a look at three different studies that introduce payoff asymmetry, payoff-irrelevant signals and changes in stake size to experiment how focal points can vary, and some ways these concepts are meaningful for decentralized oracle networks.

Payoff Asymmetry

Crawford et al. expose how under symmetric payoff conditions (subjects earned $100 when simply coordinating) 90% of the subjects coordinated on the focal point. The percentage would be significantly reduced if an asymmetric payoff was introduced (subjects would win $100 when coordinating on the focal point and >$100 when coordinating on the non-salient option).

This study proves that some bribes could have an effect on oracle coordination, which means it’s useful to understand attacks regarding bribers or entities that want to have control over the vote outcome and will do so by introducing different payoffs to the network, as they can alter the conditions of the coordination game designed. The P+epsilon attack is an example of what this type of asymmetry could mean (voters’ Schelling point changes from the truth to the briber’s desired outcome).

Payoff-Irrelevant Signals

Isoni et al. point to the power payoff-irrelevant signals (that is, signals that don’t involve a higher financial reward for the players) can have in Schelling coordination games that model tacit bargaining — independent actors perceive a conflict and anticipate others’ behavior without communication.

In their work, based on a game where players allocate an object to one place or another, the non-monetary properties that influence players’ decisions are closeness (distance) to an option, and accession (shared properties between items). We can relate this data to the double agent incentive we mentioned before. If all voters trying to be convinced to lie perceive, without communication, that the rest of voters will lie too, we need to provide an incentive for them not to if we want to ensure the efficiency of the network.

Stake Size

Parravano et al. introduce stake size changes in order to experiment how these changes affect coordination on focal points. How does the size of the payoff vary players’ coordination rates? Interestingly, their data shows that in symmetric games, coordination on the salience increased with stake size. The bigger the payoff, the more players agreed to choose the focal point.

By contrast, in asymmetric games (introduced above) coordination rates did not vary with stake size. Although players coordinated less on the salient label than in symmetric games, they were more consistent with their choice with little regards to the sizes of the payoffs.

These results could lead us to believe that in asymmetric games (those where a briber tries to change the oracle’s vote, for example) the size of a bribe will have little effect on how much coordination changes due to the bribe itself. Experiments can always vary given conditions, so we’ll have to see how players act once oracles are fully deployed.

Closing Thoughts

We started by challenging ourselves to think if Schelling coordination schemes were the right approach to seek consensus in decentralized oracle networks. Throughout the examples, we have seen that Schelling points provide a strong, low-effort, high-reward incentive for voters to agree upon a given solution.

It’s important to consider that concepts like focal points, introduced well before computers gained mass adoption, are now a key foundation for the design and implementation of crypto-economic networks like oracles.

These networks must be built to survive in hostile environments. As we have seen, attacks can bring high reward if not addressed with the right incentive mechanisms. Schelling coordination schemes provide the basic layer for seeking truth between unknown trustless parties. We will continue to research and develop around how to strengthen this approach with properties like voter and claim anonymity on every epoch in order to avoid collision attacks that could end up being very harmful for a given oracle network.

References

-

TruthCoin: Peer-to-Peer Oracle System and Prediction Marketplace

-

Focal points in tacit bargaining problems: Experimental evidence

-

Stake size and the power of focal points in coordination games: Experimental evidence

If you’d like to connect,

.

Thanks a lot for reading! You can also:

- Kauri original title: On Oracles and Schelling Points

- Kauri original link: https://kauri.io/on-oracles-and-schelling-points/560693efab534c97a8f97b251984773d/a

- Kauri original author: Witnet (@witnet)

- Kauri original Publication date: 2018-11-20

- Kauri original tags: none

- Kauri original hash: QmPir8GubfJrCQE2xgrtLQjtVrktf7gA63bx8dBqnNf8VN

- Kauri original checkpoint: QmYRYAA1TRyDiXS6uLXdt6qS8AnW63tqJHYpUQKrdyNz7h